The Accessibility Scotland 2019 theme was Accessibility and Ethics. Ashley Peacock @Time_Is_Ticking spoke on the topic – Design to build bridges – when to use disability simulation.

The Accessibility Scotland 2019 theme was Accessibility and Ethics. Ashley Peacock @Time_Is_Ticking spoke on the topic – Design to build bridges – when to use disability simulation.

How do you design products when your user’s think and experience the world so differently to you?

In autism there exists the “Double empathy problem” – the idea that autistic people cannot understand us and we cannot understand them.

Too often co-design questions are structured in a way that render inaccurate results from interviews.

So, how do we bridge these differences in order to work together towards better and more accessible tools?

This talk will be on the ethics of disability simulation as a means of understanding user’s (when it is and isn’t ethical to use) and how to build an adaptive co-design process based on different user’s needs that enables a common shared language which may in most instances be a better approach than disability simulation.

Video

Slides

Design to build bridges: when to use disability simulation (Powerpoint)

Transcript

So, thank you very much for Accessibility Scotland to invite me here.

I get to talk for 50 minutes straight on topics that I’m super passionate about.

And so, I’m the founder of a company called Passio, and at Passio, we focus on designing tools and technology with the goal of a more inclusive world. We work with universities, businesses, Innovate UK and also charities.

Today, I’m going to talk to you about three different projects with very different co-design needs and requirements.

Common theme throughout this talk is that there is no one size or approach to solving co-design challenges.

So the first thing that I’m going to talk about is something known as the double empathy problem.

Well actually, first of all, why co-design? That’s a good start.

So I had an interview once before and someone said that there was this pub and they spent thousands of pounds on making this pub as accessible as possible.

The toilets were amazing. The layouts of the pub was incredible, but there was one problem.

No one checked to see if the entrance to that pub was accessible. And so they spent all of these funds and no one could even get through that door.

So the topic of why co-design from my perspective, it doesn’t matter how much experience you have, your users are the ones who are the experts.

So the people who spend every minute of every day experiencing their condition, and so it’s really important that we consult with them.

So the first thing I want to raise here is something known as the double empathy problem.

So there’s this common notion in autism that there’s a lack of something known as theory of mind.

This idea that people on the autistic spectrum can’t empathize with others.

As what the double empathy problem it says,

“It is not the autistic people can’t empathize, they can understand their own communities really, really well. They just struggle to understand neurotypical communities. But the opposite is also true. Neurotypical people struggle to understand autistic communities.”

So in the context here of co-design, if you’re communicating from two different worlds, a part of your goal is to bring those two worlds together, so that you can work together on creating solutions.

And so the term was coined by someone called Damian Milton. He’s an autistic researcher, and he says,

“This framing emphasizes how communication and social encounters are always things that happen between people, meaning that any breakdown in communication is always relational and down to both sides, and not just in any issue with one another.”

The next quote I have here is from Donna Williams. She’s an autistic person, and she says,

“Right from the start, from the time that someone came up with the word autism, the condition has been judged from the outside by its appearances, and not from the inside according to how it’s experienced.”

And so that might lead us to think, well, maybe there’s a way in which we can understand from the inside.

So, I started on a project to create a 3D autism simulation tool. And the reason that I started this was because for someone who has a lot of family members on the autistic spectrum, I was trying to think about what I might need, what kind of tools I might be able to create.

And I realized that with 20, 25 years of experience of this, for me it was to really hard to imagine.

So, I went about trying to create a simulation game essentially so I could get a better understanding and therefore also understand my family much better.

The goal of this was to teach teachers, maybe mental health professionals, maybe public sector workers, like a lot of groups who maybe get one or two days of training, and then they’re just kind of put into the environment and expected to know and be able to support people with different needs.

The goal is just to educate people with autism, but not to try and stay away from the idea that if I play this simulation I’m going to understand everything there is to know about autistic people.

And it was to encourage people to ask questions, because that I think is probably the best way of fusing the two different worlds essentially.

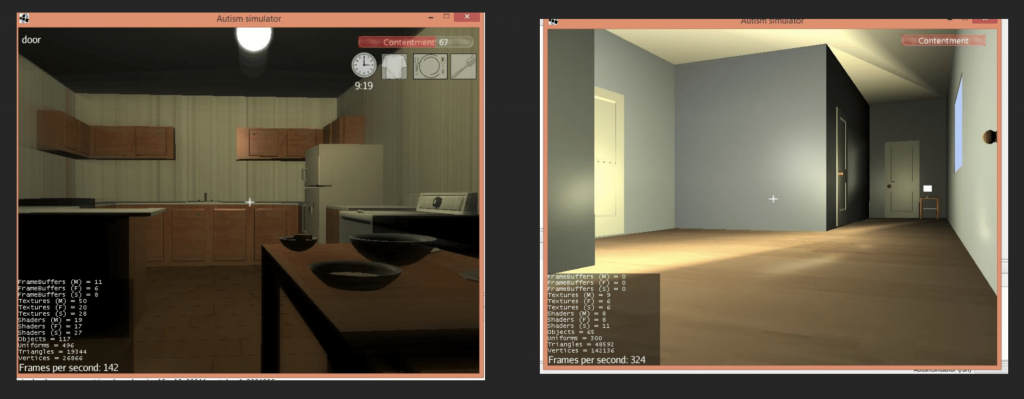

So I do have a video of this, that if I have time, I will show it, but there are here are just two simple pictures.

On the left here we have the kitchen, we’ve got fridges, and there’s a variety of different smells that will come up, and then on the right, I’ve got an image there of the hallway.

So as I was going about this process, as most people might do when they start a project, you start off with some interviews and you try and understand the experiences.

Maybe if you have your users, you try and understand the problems that they might be encountering.

But I noticed that I was getting not … The responses I was getting more kind of a couple of words. I’d ask them questions like,

“What’s your daily routine?”

And they would tell me their daily routine, but it wasn’t really enough to help me really understand them.

So I went to a group of autistic people, and I asked them about this and they said,

“Oh, your questions. Well if you ask black and white questions, you’re going to get black and white answers.”

And so the suggestion was that I change the way in which I was asking these questions.

So instead of asking,

“What is your daily routine?

What challenges might you encounter when completing your daily routine?”

The problem with those kinds of questions is I’m already automatically assuming a particular answer.

And so if I asked you what your favourite colour is, I’m already gearing you towards responding with a colour.

Maybe you don’t have a favourite colour, and so therefore, how would you ask that question?

So what we tend to get is that people, when you’re interviewing them, will focus on giving you an answer just because they think it’s what you want to hear.

And so therefore, when you’re running these kinds of interviews, you might not actually be getting the information that is genuine and useful.

So, I was told to remove the interview script, which for anyone doing research, it’s pretty terrifying because it’s kind of hard to collect your data when you’re not following, or to analyse your data when you’re not following any particular script.

A suggestion was, instead of asking,

“What is your daily routine?”

Is just to ask someone,

“What is a successful day look for you?”

To then also focus on using themes and then to focus on using questions that would just prompt more discussion and then to kind of have small focus groups and just to kind of facilitate those discussions.

And the final one is to get the community to actually ask the questions, because who understands the community more than the people who are in that community.

And I’ve seen a really interesting research method used at Edinburgh University where they did this.

They got everyone to ask the questions to the group, and then they would work out the most commonly asked questions and they would pose those back to the group, and then they would iterate on this process.

The responses that I started getting became really detailed, and just things I absolutely would never have imagined.

So to read out a response here that I got.

“I was just so traumatized by the time I got to school with all of these different noises, smells in the car, an overload of sensory information.

The woman in the front seat had this horrific perfume that stinks so badly, I tried to hold my breath and I would start to feel dizzy.

I just sit there in silence in the back seat. I felt so traumatized by this drive to school, and I couldn’t explain to anyone around me what was going on.

When I finally arrived home, it all just came out as anger, rage even, and my parents never knew why.”

So after pulling out this information, I have an image here on the left, which was the interpretation I was picking up from interviews, of what a sensory overload might be for an autistic person.

And then I would give it to them, and they would say to me,

“You need to make it worse.”

So this image here, that we have on the right is actually closer to their experience.

So what I started doing is letting the person change the settings, so that they can literally create their personalized experience because every person is different, and then they could give it to other people so they can explain, for example, why I can’t use particular clothing, or why I need to not be in an open plan office.

Actually, I’m going to play that video now, just to highlight this. So this video is not coming up on the screen actually. I’ll play that after.

Okay. The second project that we worked on was a public transport assistant.

It was for four different user groups, people with dementia, visual impairment, wheelchair users, people who are hard of hearing.

And the idea is to take some of the challenges that people might encounter, and to see if we could find a technology solution for this.

One of the design challenges with this is that, the environment changes so rapidly. The weather can change it. The person’s mood on the day who’s a staff member can change your experience of public transport.

There’s all of these things that make it really difficult to control for. And you also need quite a lot prior knowledge to go about this.

So one of my first thoughts was, well, maybe I might try and go in a wheelchair and go around the public transport for the day.

And in my head I’m like, I know it’s not going to be the full experience, but maybe it’ll give me just a bit more understanding to ask the right questions, when it comes to interviews and I’ll have a bit of understanding so we can kind of again bridge the two worlds.

However, when I asked this, a lot of people were against it. So instead what we decided to do was shadowing.

So we would interview people, and they would take us on their journey through public transport, and they would pinpoint all the things that were coming up for them quite frequently.

I’m so glad that we did this, because if I had have gone in a wheelchair, I probably would have been really tired trying to get around after the first half an hour.

One person said to me that,

“One of the strategies I use is I can wheelie up the curb. You’re not going to be able to do that if you’ve only been going around in a few hours.”

And so the focus would have been a lot of confusion and trying to learn how the systems around public transport were working, rather than the focus on their experience of what it’s like on a daily basis to get through public transport.

One of the great things of doing this very early on, before we’d even started designing the application, we did shadowing.

It broke our assumptions pretty early on. I thought,

“Well if we can design for London, then we can probably design for anywhere in the UK.”

Turns out London is really accessible and places in Scotland are not so accessible.

And so straight away that was good, because we could have eradicated that part very, very quickly.

Another opportunity meant that we were able to ask people about their experiences in the moment.

You know, I was able to observe and feel some of the stress and annoyances that people were having.

And of course the more you learn, the more and the better questions that you get to ask.

And so, have one example here, which …

So we started with like kind of pre-interviews and then we went gone to shadow them.

And this is a great example where on the left here, we’ve got a wheelchair sign, and then we also have …

So it’s basically indicating that this should be where you board the train.

And after three attempts with an electric wheelchair, an electric urban wheelchair, so it’s built for the city, we couldn’t get on the train.

Eventually, guards came and the first response was,

“Oh it’s a problem with the wheelchair.”

So these like really small things that probably happen quite often, just weren’t coming through in interviews, until we were able to go with them and to kind of see some of these quite frequent occurrences.

This brings me on to a third project.

And in this project we were working with users who have a really, really rare form of dementia.

It’s called posterior cortical atrophy.

There is about 30 people registered in the UK with this condition.

They don’t have stereotypical dementia symptoms that we might think about.

The first symptoms that they get is dyslexia, then they have visual processing challenges that starts relatively early on, and they also have kind of these conflicting requirements.

So they might not be able to read headers in newspapers, but they can read small text fine.

But then, if you’re someone who has glasses, then I mean how do you solve for that?

So the goal of this project was to help people with posterior cortical atrophy basically to be able to read again.

Some other challenges that we encountered is, for the people who have this, it becomes quite difficult for them to visualize what they need, it becomes difficult for them to visualize a model of the application, they have problems of visual spatials, they can’t orientate themselves within the application.

When we were first working with these users, we weren’t sure if they would even be able to turn the tablet on, let alone be able to read it.

It was a project with the University College London, and it was good.

They started off, first of all with a bunch of research, where they had basically made this kind of reading layout here, and they realized that if you had this fixation box and the word in it, and then a second word here, you could move the words into the box and the person could read the words actually pretty well.

The problem was that it worked in theory. When that research was done, their person was able to read the words, but it just didn’t work in practice, because it’s really hard to read things, two or three words at a time.

So after a sequence of going and speaking to the users, coming back and thinking of more different text presentations and then going back to users again and keep kind of iterating through that process, we actually got pretty lost and we were working with …

The researchers had kind of 10, 15 years of experience in this and we just couldn’t find a solution to this problem.

In this context, things like shadowing is less useful.

You can observe someone’s challenges as much as you like, but doesn’t help you really understand them.

And because of the conflicting requirements, it makes it really difficult to again imagine or simulate or approach it from that direction.

So instead, what we started doing is focusing on people’s coping strategies and their coping tools.

People started sending us in diagrams of text for the best presentation.

So we started implementing those, and then we made the user interface as adaptable as possible, so that essentially users were able to recreate their best reading experience on the tool.

This then went through a trial, and the results were pretty positive.

This is a diagram of one of the tech’s presentations, and some of the strategies that people would say to us, is they would get a red piece of card and they would cut it out, and then they would stick it kind of over the newspapers, so they would have this window.

And so we designed it with this idea of having that window. Then users could choose where they wanted to keep his fixation box line.

They could have it read out loud if they wanted to.

They could have three words in a line.

Every kind of text presentation that you can imagine was implemented here.

We iterated, there are some settings that we removed because they weren’t as required as we first thought.

So, we have three projects here, three different strategies of trying to understand users, so that we can create something with the most value and the most benefit.

In the first, we found that interview approach and communication was one of the key things.

That idea of being able to simulate didn’t work too well with public transport, because the environment is so different and it’s really difficult to predict.

And so we asked users to take us on their journey.

And then in the third example, it’s even more impossible to do any of those things, so the only thing that we could do is to essentially create a platform for them to create their own solutions.

I feel like it’s a very important part of design. It’s not, you going and getting some expertise and then implementing it into your project.

It’s creating that bridge, so that other users can essentially create what it is that they need through you.

What we learned from all of this is that, first you can co-design your co-design, and so what that means is you can come up with your methods and you can …

It’s pretty good to trial it with your users first, because if you think you’ve come up with a good method, for example, and went to simulate what it’s like to be in a wheelchair and go through public transport, and you think that’s a great approach, and then you realize much later that it kind of falls down, it’s really important that you consult with people before that happens.

Something here called a Delphi Study, which is again, where you ask other people to come up with their own questions, and maybe you encourage them to come up with the cortisone process.

And there’s a great article here that I really love and it’s from one of my supervisors who was at Edinburgh University, Sue Fletcher Watson.

And what she does is even before the grant applications go in, she consults with a mentor.

So she has a weekly session with a mentor, and they’re able to direct the focus or the direction of her research and her grants.

Because she picked up that, it’s quite common for people to,

“Oh, I’m going to do some co-design and I’m going to do that, and I’m going to go and chat to someone and ask about their stuff, and get some feedback, and then kind of pat myself on the back about this brilliant co-design process that I’m using.”

So it’s quite important again, that we really merge the co-design part of the processes that we’re doing. And this is one great way of doing that.

So in summary, it’s important to design by trying to build bridges with the communities in which we’re working in, learning how to understand, how to communicate and learning how to ask the right questions.

It’s important to get users involved as early as possible, before you even start doing your wire frames and start doing your design.

And to also remember that users will always be the experts. It doesn’t matter how much experience you have, there is always something that you can learn.

And even now for me, with all of these experiences, there are so many things I learned about the autistic world that totally changes the way in which I think about design or building software.

And another thing of course is to remember that every person is different.

Just because you’ve got autism doesn’t mean the same person with autism is going to have the same problems.

So one of the things to keep in mind is how you can build your tools to be as adaptive as possible, and working with groups to make sure that you’re choosing the right adaptions.

So this video is of an autistic person playing this video game and then commentating on their experiences playing the game.

So I’m just going to skip a couple of seconds first.

Anyway, let’s get on with it, shall we? Right, here we go. Let’s begin.

(Movie starts – young man using simulator is speaking)

Welcome to my world, which of course is the autism world.

We’ll go into mission mode. Wow, let’s live a little.

Your task this morning is to complete your morning routine, which is eat breakfast, brush teeth, get dressed with all in 40 minutes.

All the images at the top right, light up as you complete each tasks.

Whoa that’s loud. Whoa, that’s loud. That’s loud. So the first thing I need to do is eat breakfast.

Okay. Oh, senses. Oh, outdoor noise. That’s really loud.

Oh, Whoa. Sorry about this way. Jeez, turn the light off. God.

Oh my God, that is … Oh, sensory overload and the smell.

Oh my God. This is so scary. Oh my God.

Oh my God. That was evil. Breakfast, which is a bowl of cereal. Not cheese, that’s why having a meltdown because I’ve picked up the cheese. [inaudible]

Oh my God. Eat. Cool.

Oh my. I believe brushing teeth was next, so.

Oh. No, no, no, no. Meltdown, meltdown. Oh my God. Bedroom, bedroom, bedroom, bedroom.

Oh my God, oh my God.

Stuff to get, stuff to get. Kitchen, food.

Right, now it’s 9:00.

9:15, brush teeth. Oh my God. I’m having a right old.

Get out of the bathroom, get out of the bathroom.

Oh my God. Get dressed, get dressed, get dressed. Get dressed, get dressed.

Yay. Oh my God. That was actually awesome. That was to play.

That was actually surprisingly quite accurate, and I’m incredibly amazed by that person’s creativity.

I was so impressed.

I think you should all give it a go.

Make sure you wear headphones because it really just gives you the most.

I was actually, when he had the overload, it actually almost felt like I was actually having one.

So congratulations to the video game maker. Well done. Absolutely brilliant.

This is something we need to share with everyone.

(Movie ends).

One of the really interesting things they had come out of doing this actually was that when neurotypical people were playing it, they started coming up with strategies that autistic people were using in their environment, and that was really interesting because it suddenly started creating the opportunity to have conversation.

One person said,

“Oh, when you play this game, I have to look down at the ground and I can never explain to my parents why I have to look down at the ground when we’re walking places. And so I would always be told, “You need to look up,” like not being respectful.”

And so suddenly having something that they had that was concrete and they could have a shared conversation around it, for them was just something that was really empowering to be able to do.

Yeah, okay. That was the end of it. So thank you very much.

If you have any questions, great.